I. Introduction

There could be many answers to the question, “How should we read the bible.” Those answers depend on the purpose for which we read, the kind of information we hope to find, and the relationship or lack of relationship we feel with a community that considers the bible its foundational document.

II. Confessional and Non-confessional Readings

First, we can distinguish between two ways of reading, each with its own goals and purposes. Let us call them confessional and non-confessional readings.

A confessional reading is a reading from a perspective of faith. The faith of the reader (or listener) is crucial in producing the desired effect. This is the kind of reading we find in church or a Bible-study group. The reader listens for the voice of God in the text and hopes to find something spiritual, edifying, strengthening, or comforting in the reading—perhaps some guidance for daily living.

A non-confessional reading does not necessarily deny the importance of faith, but has different goals. It’s a kind of reading that can be done by any informed reader, regardless of her faith perspective or lack of faith perspective. It’s the type of reading often found in university classrooms. The reader has different expectations from those of a confessional reading. A non-confessional reading may be done to find historical information or to better understand ancient cultures, for example, without assuming that God will or will not speak in the process.

Often a non-confessional reading can help provide insights into the setting of the Biblical texts—the history of the period in which they were written, the societal values which they reflect, or the structure of the texts themselves—which can be extremely relevant for a later confessional reading. We will spend much of our time in this class attempting an informed non-confessional reading, which we may occassionally use later to inform a confessional reading.

III. Synchronic and Diachronic Perspectives

We may also distinguish between synchronic and diachronic approaches to the biblical texts. A synchronic reading looks at the text in relation to the specific time in which it was written, not in relation to the historical events that lead up to that time. A synchronic approach might ask about the values of the society in which a particular text was written. It might look at other texts written at the same time period in that same society to see what light they might shed regarding the form of literature that the text represents. A synchronic reading might also compare the thought expressed in a biblical document to that expressed in other documents written in the same period to see if the biblical text reflects perspectives that were commonly held at the time or if it challenges those perspectives.

A diachronic approach, on the other hand, sees the biblical text as a part of a historical process and asks questions about the historical events which led to its writing or which shaped the times in which it was written. It treats the antecedents to the events described or assumed in the Bible—the events which came before them and are considered important in determining their significance.

We will use both synchronic and diachronic approaches in this class, and I will attempt to make clear to you when I am using which one.

IV. The Literary Setting

Any informed academic reading of the biblical texts must also include an awareness of the types of literature found in the Bible. Poetry cannot be read the same way as prose, but both are present in the biblical texts. Parables are not the same as letters from a pastor to a church, but both are found in the Bible. As we approach each of the biblical documents I will have something to say about its literary form and what difference that makes in reading the document.

Besides an understanding of types of literature, though, an informed reading of the Bible should include some knowledge of the historical production of the literature found in the Bible and the process by which these particular documents and not others were chosen for inclusion in the Bible. An informed reading should also include an awareness of how the biblical texts were passed down through time and translated into our language(s). We will discuss these issues as well, and you will read more about each one.

More information on the literary setting of the Bible is provided in the chapter, “Literary History of the Bible.”

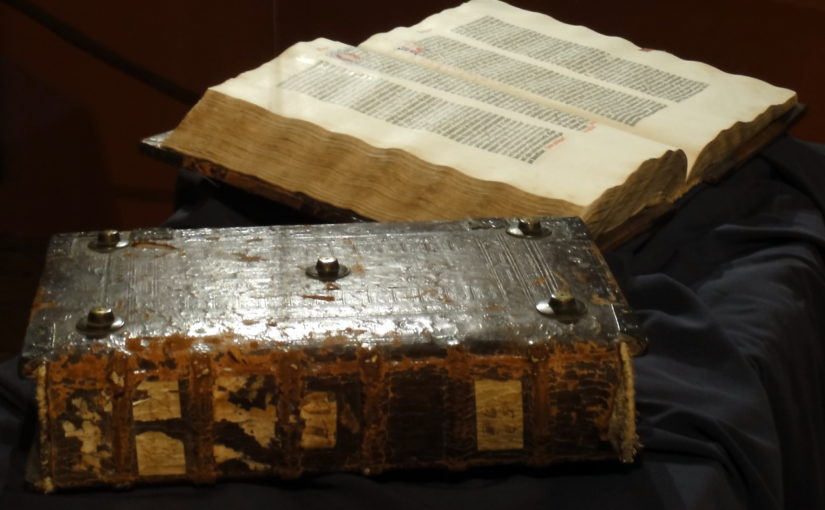

Photo credit: The featured image at the top of this page shows the Gutenberg Bible (Pelplin copy). The image, which is in the public domain in the United States, is taken from Wikimedia Commons.