Canonization, transmission, and translation all impact the level of confidence readers may reasonably place in the accuracy of the biblical texts. How should this knowledge be related to one’s view of the authority of the text?

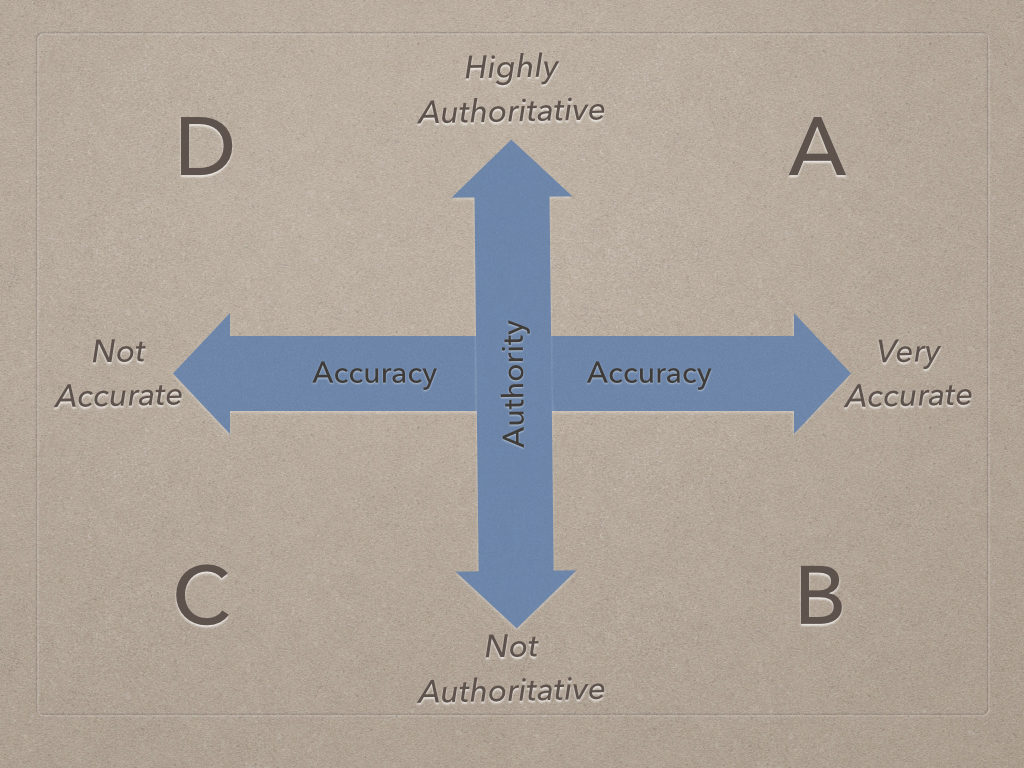

While some views of biblical inspiration claim that the authority of the text is directly dependant upon its accuracy, the issues of accuracy and authority are not necessarily directly tied to each other. Examine the following graph of views of the accuracy and authority of the text.

The letters A—D in the image above represent different views on the accuracy and authority of the biblical texts. A person whose view of the text is represented by point A on the graph might say something like this:

The text is extremely accurate, and for that reason it is extremely authoritative. If the Bible says don’t commit adultery, then I must not commit adultery because I believe firmly in the authority of the text.

A person whose view of the text is represented by point B might say something like this:

Yes, the text is extremely accurate. We have an amazing number of manuscripts that provide us with a wealth of information about the exact wording of the text, so we can do an unbelievably accurate job of reconstructing the original text.

This person, though, might commit adultery, or steal, or do other things prohibited by the text because she or he does not attribute any authority to the text. “It may be accurate,” she might say, “but so what? Who cares anyway?”

A person whose view is represented by point C might say something like this:

We can’t possibly reconstruct the biblical texts accurately. There are thousands of manuscripts and none of them are identical. How can we have any chance of doing an accurate job of reconstructing the original text. And even if we did, how could we know that the translations available to us accurately represent the meaning of the original. Look at the differences between them. Surely you can’t think that they all accurately represent the original text. Which one is right?

And after making this argument she or he would ignore the advice and council of the text, assuming that an inaccurate text can’t possibly have any authority.

A person whose view is represented by point D would say something like this:

I don’t believe we can really know what the original text said. At least not the exact wording. The evidence is just too diverse. And yes, I know there are serious differences between the translations, and I don’t really know which one is best. But for me it really doesn’t matter. When I read the text I hear the voice of God. The text doesn’t have to be perfect for God to use it. God uses poeple who are not perfect. Why can’t God use a text that is not perfect. When I hear God speak, even through an imperfect text, I know it is the voice of God, and God’s voice has authority for me. If God says, don’t commit adultery, then whether he said it with an active voice verb or a passive voice one, it still means don’t do it. So I’m not going to.

The issue of the authority of the text is fundamentally an issue of faith. It cannot be proven or disproven by examining the history of canonization or transmission or translation. Still, failure to understand the processes of canonization, transmission, and translation can easily lead to inauthentic faith based on false assumptions.

Related Pages